http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2012/09/d-t-max-on-david-foster-wallace.html

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2012/09/d-t-max-on-david-foster-wallace.htmlThe above is a link to a bit of audio on the New Yorker website from an interview concerning the biography, the cover of which is in the top left corner of this post, that has just been released by D.T. Max. Four-years after his sudden and unexpected suicide, American novelist David Foster Wallace is being remembered by a special on the New Yorker titled "D.F.W. Week". The special is particularly focused on the writer, using his writing as a means of gaining insight into who he was. In terms of formal literary criticism, this process is totally backwards and the whole thing is a little eerie and weird, considering all this speculation into the life of an author, who was clearly a troubled person and a private professional, seems to be a lot of hearsay and guesswork. There is even some praising of his poetry which he wrote when he was seven (http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2012/09/dfw-week-childhood-writings.html). But considering the enormous amount of attention this writer is getting totally separate from the content of his work, I thought it might be interesting to write about why we care about him and artists like him, when their personal demises are so defeating. My purpose in writing the following was to try and understand why D.F.W. week exists at all.

I know you know the old parable of the tortured artist who goes through life under-appreciated only to be universally heralded as a titanic genius after death i.e. Kafka, Van Gogh, Dickinson, Poe, etc. Right? It seems to me that the most susceptible subjects to this kind of after-death popularity boom are those artists who, as "victims" of their craft/lifestyle, either waste away from drugs, violence, negligence, starvation or actually commit suicide. We are especially interested in these cases because once the artist has actually died, then we can look at an artist's work with a lot more faith. For instance, lets say someone who is predisposed to absolutely hate The Dark Night upon first watching (a staunch pacifist perhaps), is told of Heath Ledgers sketchy pseudo-suicidal death that followed in the aftermath of the film, will almost certainly give a lot more patience and respect to the film due to the knowledge that a major contributor to the movie died doing it. It may be possible to detect the clues of the artists agony on screen, possible maybe to understand and diagnose the pain that is unsettlingly foreign to the viewer. It almost adds an ethereal puzzle to the experience.

The point is, we the audience find each other's deaths thrilling. Probably because we are thinking of our own death or something similar. And those who die ignorant of the great fame they are about to achieve, are seriously intriguing to us because they assume a martyr status. The pitiful souls who toiled and died struggling to gain our attention and respect; all because they merely felt compelled to tell us something for which they were never rewarded.

Of course, this process is only natural and necessary. In the convoluted traffic of art and ideas in the contemporary, overpopulated world time is, more than ever, the ultimate judge of an artists's success. History must remember it in order for it be great. And so maybe the strongest allure of the post-mortem superstar for those of us who live beyond him to witness his fame-explosion, is that he represents a tie from our generation to significant history. We do claim them. Just like I feel a totally irrational pride that Michael Phelps swam at the same pool I did when I was a kid, all societies claim their prized figureheads as intimate acquaintances in their memory and character. As American's we can all claim pride for the accomplishment of our already established historical greats. But we cannot defend the same personal connection to the Abe Lincoln, FDR, or MLK without having experienced life under the same conditions in which those heroes experienced it, as we can to say Kurt Cobain or Barack Obama, because the latter pair did what they did in a world in which we have first hand experience and understanding. One of our great authors, David Foster Wallace, having died young a decade after publishing a groundbreaking novel and having started to receive attention as a literary great, is a perfect someone for to be claimed as an idol of 21'st century life. The reality that all his success led him to suicide does not disqualify him. In fact, perversely, it feeds his celebrity.

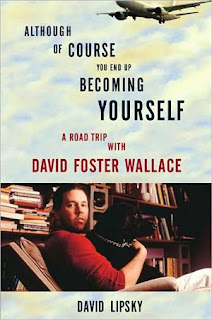

Yet, maybe those who know Wallace's work just want to know Wallace, want to feel closer to him. Following The New Yorker's D.F.W. week, D.T. Max's biography, or David Lipsky's poignant Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself allows us a glimpse into what Wallace was like at certain moments in his life. The conclusion of all these tends to be: doomed, oversensitive genius

But having read a lot of this extra biographical stuff about this author, whom I admire a great deal, I really don't think their is any sort of satisfaction to be gained, no answer to the puzzle of his life, no lesson to be learned from his suicide. In the end, I think if you really want to understand the artist you have to look at his art. That's where he expressed himself most seriously. He wrote a big book titled Infinite Jest that you might have heard of. It is widely accepted by scholars and critics as a masterpiece and one of the best post-modern books ever written, having garnered a passionate cult following and a healthy amount of responsive literary criticism. I think Wallace's fiction should be remembrance enough for all of us.

But having read a lot of this extra biographical stuff about this author, whom I admire a great deal, I really don't think their is any sort of satisfaction to be gained, no answer to the puzzle of his life, no lesson to be learned from his suicide. In the end, I think if you really want to understand the artist you have to look at his art. That's where he expressed himself most seriously. He wrote a big book titled Infinite Jest that you might have heard of. It is widely accepted by scholars and critics as a masterpiece and one of the best post-modern books ever written, having garnered a passionate cult following and a healthy amount of responsive literary criticism. I think Wallace's fiction should be remembrance enough for all of us.Still, it is oddly thrilling to learn about the author's bad chewing tobacco habits, his nervous misdemeanor, his drugs addictions, his failed love exploits. Once we know this stuff, he becomes a guy who accomplished something big whom we can imagine as a friends older brother, or an older in-law, that we sort of know. He is no longer remembered as just an unfathomable intellectually superior literary giant, but also as a normal human being. A contemporary American man, riddled with angst and modern thought-paralysis, who contributed something incredible to literature. Could it be that this is a more honest way for history to remember our geniuses? Not as miracles but as people who struggled through their work, and didn't stop until death. If so, then I'll concede to these biographies and tribute weeks, they are worth reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment